This note was written around Christmastime 2021 (hence the Christmas theme) as my initial thoughts after figuring out that predictive coding networks could be straightforwardly adapted to perform causal inference. I intended to write this up into a proper paper and do more experiments verifying it works at scale as opposed to in these toy exmaples. However, I never got around to doing so and now it seems unlikely that I ever will. I think this is an important finding that hasn’t yet been really recognized in the predictive coding literature. Because of this, I thought it would be valuable to share freely in case anybody finds it interesting. If you are interested in building on how to get PC networks to do causal inference and (ideally) learning, then please message me. I’d be interested in collaborating! The code for the toy model simulations can be found here.

One thing I noticed over the weekend is that it is very straightforward to adjust the inference procedure in predictive coding models to enable causal inference instead of just standard conditional inference. It is well known that correlation does not equal causation. The work of Pearl and others has gone a long way to providing a mathematically precise definition of causation and quantifiable ways to calculate causal influences and perform causal inference. The key that allows you to do causal inference is to have a causal graph (aka a probabilistic graphical model) of a system beyond just the joint density of data from a system. With this graph, we can formalize and reason about causal interventions – i.e. some outside force such as you intervening on the system in order to set certain variables to certain values. Crucially this is different from just observing that when certain variables take certain values, other variables tend to have other variables – i.e. correlation.

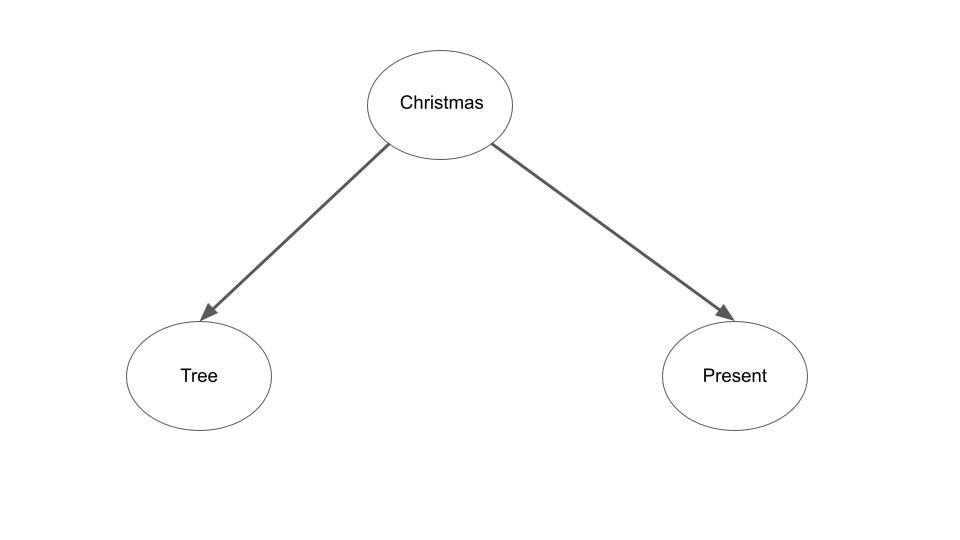

To start with a festive example, we know that when it is Christmas-time, there are often both Christmas trees and Christmas presents. This means that we observe a strong correlation between the presence of Christmas trees and the presence of Christmas presents. As such, if we observe that there are Christmas trees, we might reasonable expect that there are also Christmas presents due to the fact that if there are Christmas trees, it is probably around Christmas time and therefore there are probably also Christmas presents: \(p(present \| tree)\) is high. On the other hand, suppose instead I intervene on the system to create Christmas trees at some random part of the year, then we should no longer expect the presence of a Christmas tree to signify the presence of Christmas presents. We denote this intervention by Pearl’s do operator as: \(p(present \| do(tree))\) and we expect this probability to be low (around the prior probability of it being Christmas time). We can formalize this notion using a probabilistic graphical model of the system

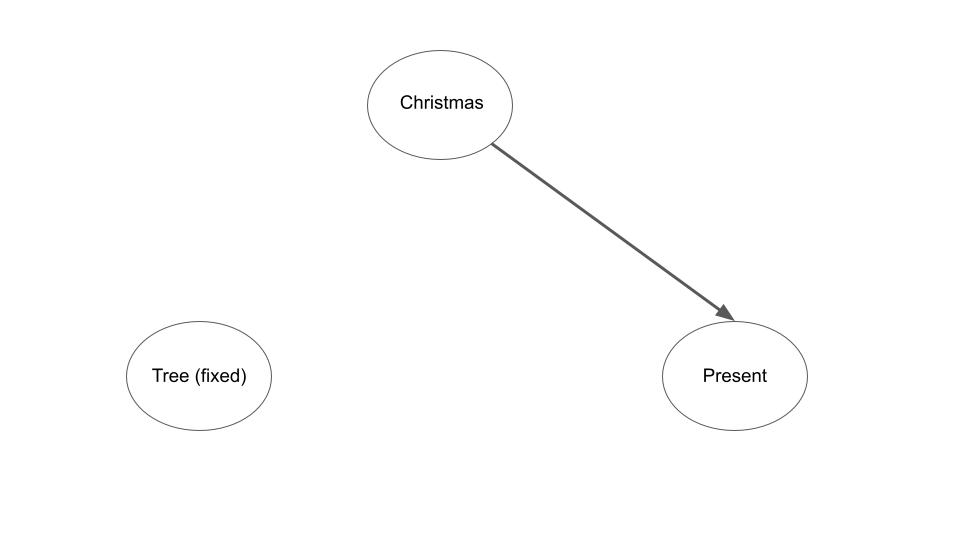

The insight of Pearl and collaborators is that we can formalize and perform causal inference about this new intervened system by simply modifying the original probabilistic graphical model to reflect the intervention. Specifically, to formalize an intervention, we fix the intervened node to the intervention variable – i.e. set the ‘tree’ node to be ‘on’ and we also remove all connections between the intervention node and its parents in the graph – i.e. the connection between Christmastime and the Christmas tree. The new ‘mutilated’ graphical model is now,

If we then perform inference on this new graphical model we see that the probability of Christmas tree is now independent of the probability of Christmas presents as we desire.

My insight is that it is extremely simple to replicate this behaviour and perform inference about interventions in predictive coding network. To begin with, when we ‘fix’ the value of nodes in predictive coding, and we take the topology of the predictive coding network to represent a computation graph or probabilistic graphical model, then we are effectively conditioning on the fixed variables. During training when we compute the activities given fixed data and labels, we are effectively computing \(p(rest\_of\_network \| data, labels)\). Given an arbitrary topology of a predictive coding network, what predictive coding is doing is a.) assuming that all nodes are gaussian distributions and b.) representing the mean of those distributions as the equilibrium activity value. When we fix certain nodes in the predictive coding graph and let the activities run to equilibrium, we are simply computing the conditional means of the rest of the value nodes given the fixed nodes.

As such, predictive coding networks standardly only compute correlational predictions. I.e. if we setup a predictive coding network with the same topology as the christmas example, and if we fixed the ‘tree’ value node to a high value we would naturally expect the equilibrium mean of the ‘presents’ value node to be increased.

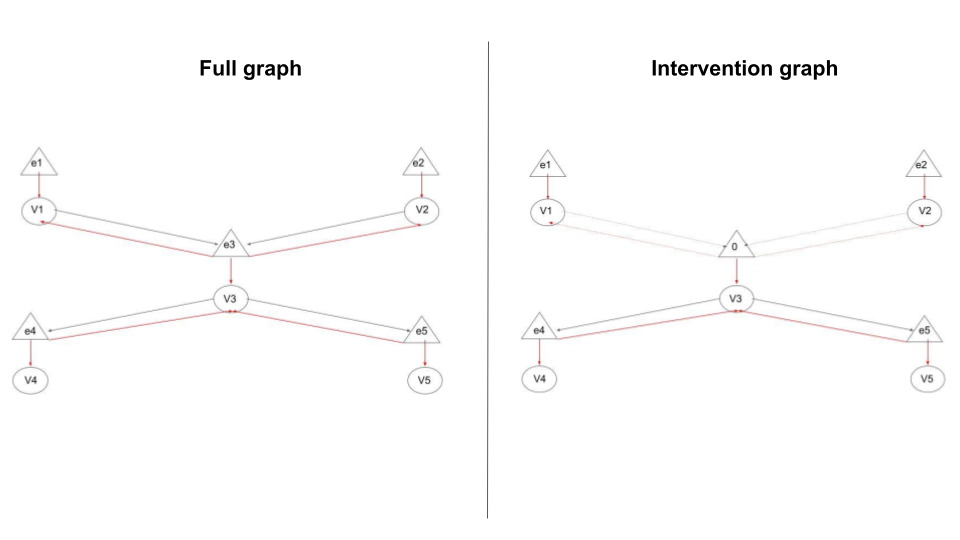

However, if we look at the way predictive coding networks on arbitrary computational graphs work, we see something interesting. Namely, that all influence of the parents of a node on the value node are mediated through the prediction error nodes. Conversely, all inference of the children of a node on a higher level node are also mediated by the prediction error nodes. However, the direct influence from a parent to a child node is mediated through the projection of the value node to the prediction error node of the child. To make this clearer, please see the predictive coding network architecture in figure 3. This connectivity scheme, interestingly, is actually perfect for implementing Pearl’s do operator in a natural fashion. When an intervention is applied, the connections in the causal graph between a child and its parents are severed. However, all of these connections in the predictive coding network are mediated through the prediction error neurons for that node. When an intervention is applied, the node can still affect its direct children, however in the predictive coding network the infleuence of a parent on its children is mediated through the value node and not the prediction error node of the parent. This means that if we simply set the prediction error node of a intervened node to $0$ then this automatically cuts off the influence between the node and all its parents – thus precisely replicating the effect of the do operator in a predictive coding network. Essentially, if we fix a value node and let its prediction error node vary freely, then we perform a correlational inference. If we fix the value node and its associated prediction error node, then we automatically compute an interventional inference.

Thus, we get the following methods on predictive coding networks for whether we want to perform correlational or causal inference:

- For correlational inference fix value node to desired value and let error node vary.

- For causal inference fix value node to desired value and fix error node to 0.

This is really nice because the necessary machinery to implement causal inference in predictive coding networks is very straightforward in that we only have to add the capability to fix error nodes to 0, and to perform any kind of inference we have to already have the capability to fix value nodes to arbitrary values. Secondly, it means we can do both causal and correlational inference in the same network and with the same algorithm just with different nodes fixed. This means that predictive coding networks can switch between causal and correlational reasoning flexibly and as required. I.e. if you observe something you can run correlational inference while if you want to imagine the effect of an intervention on the model (i.e. for planning) you can just instead run causal inference. This is a really nice property! Which standard deep learning ANN definitely don’t have. This also fits in with what we know about generative models in the brain which definitely do have this property in that phenomenologically we seem to be able to perform both causal and correlational reasoning. Moreover, this flexibility allows you to perform conditioning with arbitrary subsets of interventional and correlational conditions in the same network simultaneously.

Results

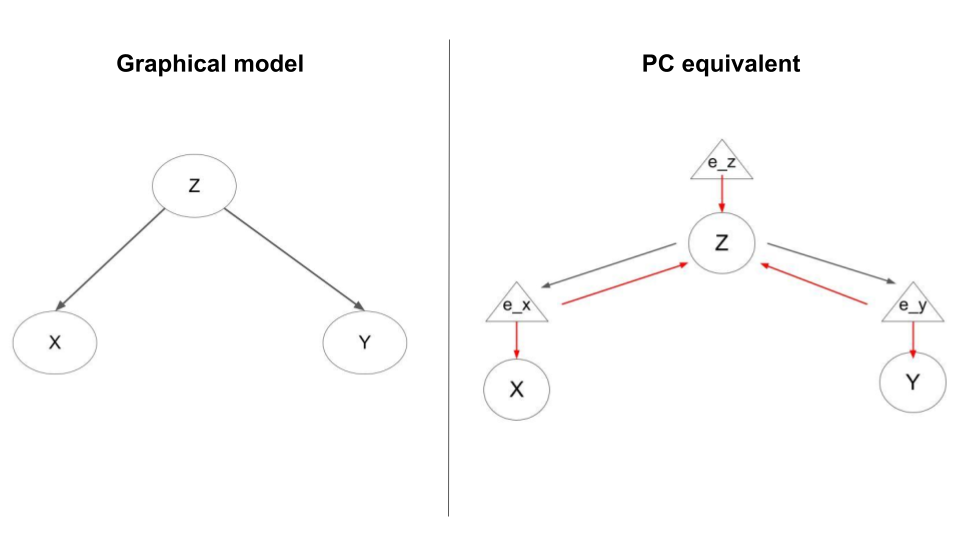

Here I demonstrate in a super simple example that this actually works. I use a simple linear generative model with the same structure as the Christmas example. We have one variable \(z\) which influences two other variables \(x\) and \(y\) in a linear fashion. Specifically, we have that,

\[\begin{align} z &\sim \mathcal{N}(2,1) \\ x &\sim \mathcal{N}(4z,1) \\ y &\sim \mathcal{N}(3z,1) \end{align}\]We can convert this generative model into a predictive coding network by defining the equations for the value and error nodes,

\[\begin{align} \dot{\mu}_z &= -\epsilon_z + 4 \epsilon_x + 3 \epsilon_y \\ \epsilon_z &= \mu_z - 2 \\ \dot{\mu}_x &= - \epsilon_x \\ \epsilon_x &= \mu_x - 4\mu_z \\ \dot{\mu}_y &= - \epsilon_y \\ \epsilon_y &= \mu_y - 3 \mu_z \\ \end{align}\]For a graph of the graphical model and equivalent predictive coding model see below:

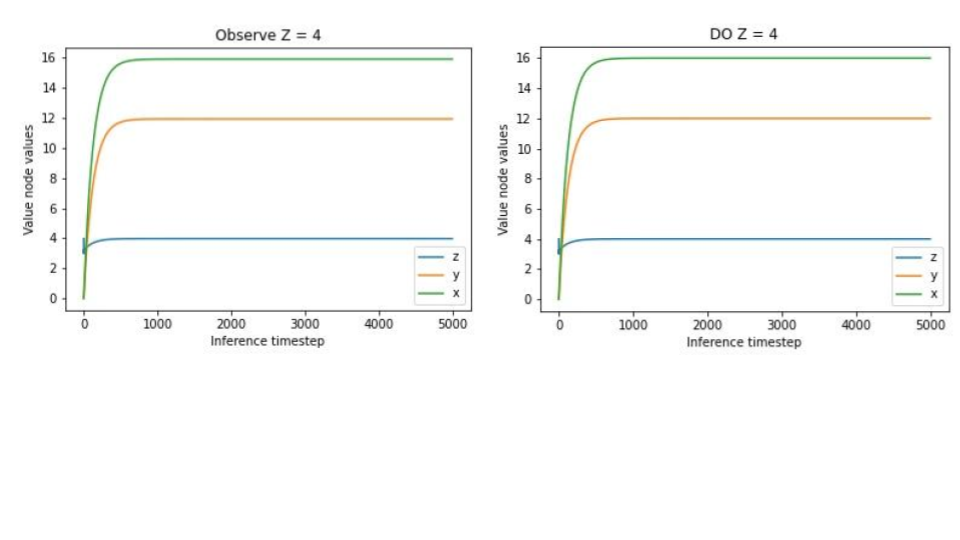

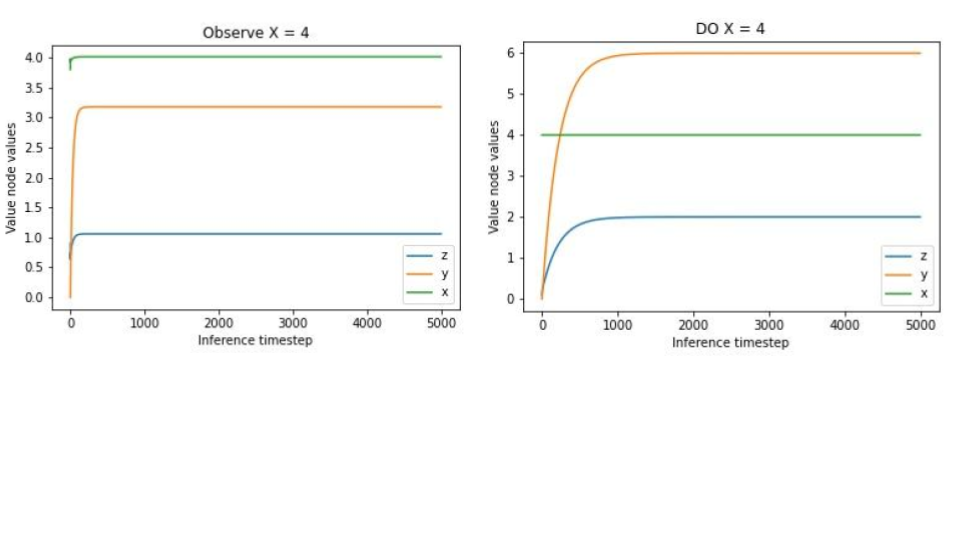

Because everything is linear and Gaussian it is straightforward to think through the correct inferences with various observations and interventions. A-priori, we should expect the mean of \(x\) to be \(4 * 2 = 8\) and the mean of \(y\) to be \(3 * 2 = 6\). Then, if we observe, say, that the mean of \(x\) is actually \(4\), then we know that \(z\) must have been \(1\) and so the mean of \(y\) is \(3\). Conversely, if we instead intervene on the system to set \(x\) to \(4\), then the value of \(x\) we now observe has no bearing on \(z\) anymore so we should expect the mean of \(z\) to maintain its value of \(2\) and so the mean of \(y\) continues to be \(6\). We verify these predictions in the predictive coding network by either fixing or intervening $x$ to 4 and seeing that the resulting inferences of \(z\) and \(y\) differ in exactly the way predicted.

Conversely, since the value \(z\) is the true ‘causal’ variable and has no parents, observing the value of \(z\) and intervening on its value have precisely the same effect. We also show that our predictive coding network replicates this effect in that exactly the same inferences are obtained whether we intervene or observe a value of \(4\) for \(z\).